The Japanese experimental guitarist Tetuzi Akiyama has commented that he felt compelled to make mid-tempo, moderate volume music because everyone around him was working in extremely loud or extremely quiet sounds. The need to rebel, in a sense, forced him into breaking old ground.

It's a similar position to the one Morton Feldman found himself in a half century earlier. With the minute having been explored a generation earlier by Anton Webern, and with his peers seemingly more than willing to adhere to the dictates of the LP, Feldman began to grow interested in creating exceedingly long works. (The similarity doesn't end there, either. As much as Feldman's compatriot John Cage is celebrated, in many ways it's Feldman the formalist, with his use of sound and silence is extremely deliberate � an exhibition of ego, as Cage might accuse � who is a truer progenitor of the new school of minimalist improvisation.)

To cite the man himself (as quoted in Give My Regards to Eighth Street: Collected Writings of Morton Feldman, published by Exact Change in 2000):

My whole generation was hung up on the 20- to 25-minute piece. It was our clock. We all got to know it and how to handle it. As soon as you leave the 20- to 25-minute piece behind, in a one-movement work, different problems arise. Up to one hour you think about form, but after an hour and a half it's scale. Form is easy � just the division of things into parts. But scale is another matter. You have to have control of the piece � it requires a heightened level of concentration. Before my pieces were like objects; now they're like evolving things.

Trio for violin, cello and piano was composed in 1980, is among Feldman's first experiments in extended duration, and is seen as marking the beginning of his late period works, from 1979 until his death in 1987. And while it's all too easy in discussing Feldman to get preoccupied with on clock-watching, the roughly two-hour Trio was followed in 1984 by the four-hour For Philip Guston and the oft-cited six-hour String Quartet No. 2. But what matters, of course, is not how long the theater is rented out for but what's done with it once you're there. Central to the Trio (and to Feldman's ideas about use of scale) is the fact that the piece is a single movement; There's no time open for a regrouping of wits or a realigning of motifs. It is a singular expression. Rather than boldly announcing the next thematic variation, then, Feldman is constantly in flux, working within palette and pace, making subtle realignments and shifts in emphasis.

In that sense, the use of repetition is far from an elongating device. The instrumentalists get locked into patterns � in unison, in succession, or sometimes in isolation � not to create scale but to explore it, as if to say "We couldn't have a mountain were it not for each of these stones."

At the same time, however, there's a curious irony to Feldman's mountain climbing. The composer also wanted to eschew the dramatic underpinnings of concert music (notably that of Boulez), and yet it's the drama of his extended works that make them so majestic, so mountainous. For duration without drama, see (for example) Warhol's film Empire, a work of a very different emotive impact than the Trio. Feldman's long pieces, in other words, are far from drones. They are filled with suspense. And in fact, the Trio is filled with murder-mystery string swells. Certainly the composer isn't responsible for the projections of pop culture, but at the same time it's hard to imagine that in 1980 Feldman wouldn't have recognized the baggage Bernard Hermann had attached to stabbing violins. And indeed, suspense is Feldman's mojo. His pace allows ample time to wonder what will happen next. No Mozartian filigrees here! The music is, literally, suspended in time.

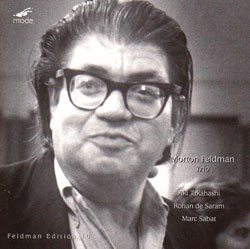

Mode's 2006 recording of the performance by violinist Marc Sabat, cellist Rohan de Saram and pianist Aki Takahashi is gorgeously warm and intimate. The only shame is that, with Feldman having despised the confines of the LP side, the 105-minute performance should be spread across two CDs. With the possibility of DVD-audio release, technology is finally catching up to Feldman's vision.

Comments and Feedback:

|