I don't like the saxophone. Not especially. It's not an easy thing to own up to since a) some of my favorite musicians (Anthony Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell, Henry Threadgill — yes, basically the wind-heavy Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians) are saxophonists; b) I came of my own jazz age in the Windy City, home of Gene Ammons and Fred Anderson, not to mention the aforementioned); and c) already implied but to spell it out, I often write about — and presumably like — jazz music.

The saxophone has been jazz's spokesman ever since John Coltrane knocked the trumpet out of the ranks, stretching "My Favorite Things" into nearly the length of an LP side and then continuing to pull at it like Richard Rodgers taffy until it lasted over an hour. It is — or has become — omnipresent, pushy, bossy even. It gets attention more often than not by demanding it. But more often than not is not always. There are still innovators (John Butcher), highly skilled practitioners (Joe McPhee) and vibrant elders (Marshall Allen). There are, in other words, players I appreciate despite their upholding of the hegemony.

And then there are saxophonists who make me question my defiance of the norm. There are saxophonists who I love as saxophonists, whose sound excites me as much as Prince's Hohner Telecaster knockoff, who I just want to hear play. Saxophonists whose dreaded horns I would want to hear even if they played the same solo every day at noon. In that class (and I've been restricting myself to the living here because come on, I'm not being paid by the word and we haven't even gotten to the record under review yet) there are but two. David Murray [whose tenor has been described (by myself) as possessing a sound somehow akin to "a sugar cube dropped in a glass of bourbon"] and Mats Gustafsson (OK, here we go), the Swedish colossus of the baritone who sounds like he's playing something as big as a barrel made of materials indescribable.

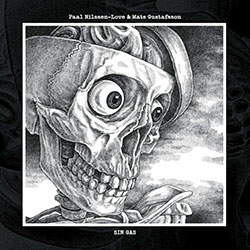

Gustafsson is, maybe most importantly, a member of the infallible and unflappable trio the Thing, with bassist Ingebrigt Håker Flaten and drummer Paal Nilssen-Love, the latter of whom is his duo partner on SIN GAS (at last), a powerful half hour recorded in Vienna in 2013 and released on the Polish label Bocian. The CD comes in a nice, gatefold cover with a lovely living skull depicted on the front and oddly enough has one track less than the LP (remember when CDs had the bonus tracks?). Even still, the CD is enough to saturate and satiate. An initial long piece that shows Nilssen-Love continually pushing, never letting Gustafsson sit still very long. It's full-on energy without sacrificing texture, differentiation or groove. After a long ride, the second piece on the CD blisters into the red, Gustaffson's already amazing tone augmented by his (presumably) yelling through it, Nilssen-Love showing just as much a signature sound on a single cymbal before, with another yell, they set off on a fast gallop.

Saxophonists love drum duets because there's nobody telling them what key to play in. It's a post-Trane indulgence that tends to flow along the same rivulets most of the time. On Sin Gas Gustaffson and Nilssen-Love show that they get that free improvisation without a chordal instrument is not license to not be interesting.

Comments and Feedback:

|