As a young(er) jazz listener in the 80s I was caught up in the excitement that met trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. After all, he was vetted by Art Blakey, whose music had driven me for years, and whose choice of sidemen brought some of the great 60s and 70s players forward. What went wrong with Wynton for many listeners, and for myself, is an interesting perspective of jazz history, a breaking point between tradition and creative freedom.

What diverted me from Wynton's music was the breadth of what was happening in improvised music at the time he emerged in the public eye. The mid-80s were a restive time, with musicians releasing explorative and conceptually fascinating albums. I followed artists like Woody Shaw, Chico Freeman, Alfred Harth, Steve Coleman, John Zorn, Dave Douglas, Jon Rose, Fred Frith; the list goes on and on, and I still listen to these players to this day. In comparison, I felt then that Marsalis wasn't a conceptual innovator, but more of an extremely technical player who also used the media to his advantage. His albums took on a tone of jazz homage, seemingly relegating it to the same realm that classical music exists in, while making declarative statements about jazz that didn't resonate with me personally. There seemed to be less future with Wynton, and at the time I didn't want to follow the safe path — there's plenty of exciting music out there to listen to! So I put Marsalis' albums on the shelf for 3 decades to pursue those I felt were more innovative players.

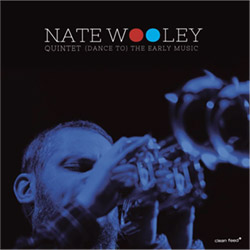

Honestly, this was a very high school attitude acted out in a high brow way, and completely unnecessary. Wynton put out a number of fine albums in the 80s. I owned them and I played them over and over with enthusiasm. They sat next to my Miles and Blue Note albums, and for a while it was a musical high. A young(er) Nate Wooley also listened to those same albums, and was profoundly influenced by them — I know this from his very clear liner notes, which are a model of honest concession about the complexities of pursuing modern music. For Wooley — and me — at that age it was about making his teen heart pound from the power of jazz music. Wooley states that this album is "simply, a person's attempt to look at his history and to remember what it feels like to be at home." He eschews any ironic interpretation of the album.

So I decided to write this review to do the same for myself. It's hard not to run a comparison between each song. Which is unfair, as few other artists would induce me to do the same, especially three decades after their albums were released. But then again, this album is an unexpected set of tunes that draws attention to itself because of Marsalis' influence on a player that few would think to compare him to: Wooley is a model of creative impulse, interested in acoustic, electronic, composed, conceptual and other outside forms. Marsalis continues to speak to the more stable traditions of jazz, producing solid but not innovative music.

So here are some comparisons. I write them because I am genuinely curious to compare the same songs I listened to 30-some years ago as interpreted by a cast of my current jazz heroes. And honestly, it seems like time to reinterpret my own feelings about Marsalis so many years later. Wooley covers tunes in the order that Marsalis released them, with numbers from the albums Wynton Marsalis, Black Codes (From the Underground) and J Mood.

The first thing that becomes clear is how much more, well, creative the arrangements, orchestration, and playing are. Everyone in Wooley's Quintet has been noted for imaginative and unusual approaches to their playing; expecting the unexpected is a hallmark of this class of player. So for "Hesitation" from the Wynton Marsalis album, Wooley puts an actual hesitation into the head of the tune, emphasizing the title. The orchestration is quite different, Josh Sinton's bass clarinet adding a textural dimension. Wooley's solos are a dream here, his smeary quick notes ripping apart the chord changes, while Harris Eisenstadt drops unexpected counterpoint to keep the listener guessing. No longer a clean jazz number, Wooley's Quintet adds depth and freedom to the soloing. Wooley actually presents two versions of this song, opening and closing the album with it. The first rendition ends with a fade and is shorter than the original; the closer offers a longer (10 minute) "Hesitation/Post-Hesitation" which gets to the solos much more quickly and allows for more interactive freedom from the players. The "Post-Hesitation" portion of the song (technically a Nate Wooley composition) slows the changes down into a dreamy haze, with Matt Moran's vibes chiming methodically as the band harmonizes over the chords.

"For Wee Folks" is a ballad from Black Codes (From the Underground), the original an accessible number with a hint of almost smooth jazz, particularly from Branford Marsalis' soprano sax. That's not a knock — it's a lovely piece. Under Wooley's hands the work is almost unrecognizable; he slows the melody down to bring it out of focus and lets the soloists emerge in more mysterious ways. Eisenstadt's drumming and Opsvik's strong pulse add an intensity, especially in Matt Moran's vibe work. The performance is more succinct, shorter, with none of the cloying quality of the Marsalis' version.

"Blues" is the only original number on the album, written by Opsvik and Wooley, and played as a duo. Wooley gets a chance to shine here, showing impressive technique but also strong emotion. Opsvik's powerful sound anchors the work, moving around Wooley's playing. It's an oddity on the record, apparently inspired by Marsalis, but shows Wooley's profound technique in comparison to the album's inspiration.

"Delfeayo's Dilemma" was written by trumpeter Marsalis for his younger brother Delfeayo, a trombonist. It features a relatively complex head that breaks quickly for melodic and relatively safe solos. Wooley immediately changes the sound for this number, opening with a mute, bringing the trumpet forward in the mix, and then takes out the mute for a strong solo that takes as many sharp turns as Marsalis' takes the straight road. The band expands the reading by 3 minutes, allowing for longer and more thoughtful soloing. Again the orchestration provides more character, with Sinton standing out in timbre while adding a more aggressive character to the piece. The band comes back together at the end with a synchronized break, yielding to an Opsvik solo underpinned by Moran's vibes. The complexity of this reasonably straight number surprises by introducing many unexpected options. It is a great example of choices afforded the modern player, showing how heterogenous styles and ideas can inform and expand upon traditional concepts.

"Phryzzinian Man" is another Black Codes tune, very much in the Miles Davis hard bop mode (straight ahead working around a strong melody). Wooley's version couldn't be further from that tradition, opening the number with Josh Sinton soloing for more than 2 minutes, veritably wringing the neck of the instrument with intensity, then slowly introducing the melody as the band joins in. The original is almost unidentifiable, with only Opsvik carrying the tuneful portion of the song while the horns and vibes repeat figures. Wooley then smears his way to a solo that growls and burns, approaching the changes from unexpected angles. Opsvik ends the album bowing on the bass, a crying figure.

"Insane Asylum" from J Mood is a piece that by title promises a bit of, well, insanity. Marsalis' solo never quite reaches the high I expected, but it's a strong number propelled by an urgent rhythm; of the other pieces covered here it is the Marsalis composition perhaps closest to early 60s Miles Davis work. Wooley doesn't actually cover that tune, but creates a perspective of it titled "On Insane Asylum". Wooley's composition is a relatively brief and more assertive effort that affords a forum for him to solo over in a trio setting, with Eisenstadt and Opsvik providing strong and wonderfully capricious support.

"J Mood" takes Marsalis' straight ahead and lyrical number that was a showcase for both his trumpet work and for pianist Marcus Robert, and gives the song over to Harris Eisenstadt for an extended drum solo. The head is given dramatic pause, with breaks from Eisenstadt, allowing the brief melody a chance to flourish, and bookend Eisenstadt's solo. The resulting gesture is only about 10 seconds longer than the original, but demands that the listener pay attention to it through unusual phrasing and a less glib reading.

"Skain's Domain" is another strong Marsalis number from J Mood, traditional in nature but featuring good soloing, with a drum solo to open the piece as Kirkland introduces the chords that lead to Marsalis' playful melody. Wooley takes the opener himself with a tour-de-force of modern trumpet playing. If any number shows the difference in approach between Marsalis and Wooley this would be it, as Wooley spits, growls, smears and plays with the horn, employing modern technique and Wooley's unique approach. The melody gets a modern update, using the quintet in ways that would have been placed on a record from the India Navigation label in the 80s.

One wonders: 30 years ago, listeners thought Wynton's solos were extraordinary. What would we have thought of Wooley that same year? How can we measure the pace of jazz sophistication? 1985 contemporary players were using the tools that Wooley employs, but would they have taken on traditional numbers the same way? Would the results have anything to do with this informed album?

In the end I find myself enjoying the trip back to my own earlier listening habits. But more importantly, I'm placated that they led to the kind of players that could update something from my simpler past in cogent and sophisticated ways. I'm not sure when next I'll put on Marsalis' original records, but I'm sure to play Wooley's new one for many years to come.

Comments and Feedback:

|