When demarcation lines are drawn between experimental and improvisational genres, when those genres are circled for emphasis and pioneers and progenitors cited, it's nearly criminal that the likes of Musica Elettronica Viva often go unmentioned. Re-listening to "Spacecraft," recorded in 1967, it's easy to conclude that if performed in front of an audience surely they were left speechless and dumbfounded once the piece closed after its lengthy trajectory. What still manages to sound radical, chaotic, and soul-shattering now, 40 years hence, must have been downright sacrilegious then; the MEV collective weren't so much pushing boundaries as inventing them as they went along, with much of the world reeling from Coltrane's blasts of interstellar consciousness and the still unresolved sound theories being bent backwards by Cage, Stockhausen, et al, on top of whatever leftover psychedelic mindmelds were altering sensibilities at the denouement of the turbulent, freeform 60s.

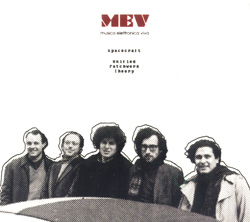

MEV at the time comprised Frederic Rzewski (amplified glass and springs), Alvin Curran (electric percussion, trumpet and voice), Richard Teitelbaum and Allen Bryant on Moog and homemade synth respectively, and Ivan Vandor on alto sax. Collectively, the quintet managed to skewer just about every notion of "proper" defined music and the vagaries of sound design, ne� the variable nature of how diffuse indeed were the commonly-held ideas of "music" and "sound." Like AMM, MEV heralded a music stripped to the bare essentials yet tightly focused and innately powerful, able to reach brutal, critical mass whenever the players chose to do so. The first half of "Spacecraft", in fact, is a jarring, galactic-rendering experience, wherein Rzewski's springs seem to eviscerate the innards of the performance space; the group's acoustic fundamental actually overshadows the later use of electronics, most of which are left to their own incidental devices and really only make themselves known in the piece's second half. Of course, Vandor's skronk never lags far behind; interspersed with Curran's exhortations, the group ends up slogging through a mass of glorious noise, invigorating, intense, and drop-dead scary, a revolutionary call-to-arms that woke up improvisatory music for the time being before it later drowned in passionless technical virtuosity.

1990's "Unified Patchwork Theory" sees the group 23 years older but no less vibrant � they still sound both of a time and outside it, blowing fierce gales of insurgency against the established musical order. Improv, particularly the British/European strain, still felt as if it was crawling out from the wreckage MEV left behind, as evinced by the group's own more proficient yet just as exhilarating contraptions. Saxophonist extraordinaire Steve Lacy now occupied the place vacated by Vandor, and Curran had brought samplers into the variegated acousmatic matrix, but that failed to diminish the compositions of their visceral impact. If any obvious changes in approach reveal themselves, it's in Rzewski's co-opting piano instead of his makeshift percussive Cages, though his ivory tickling doesn't abandon the same sense of playful disregard he exhibited decades back. Teitelbaum and Curran's synths spurt and splatter across the sonic canvas with Pollock-esque moxie, splashes of color augmenting the trails of brass; one can easily glean the antecedents that no doubt informed Thomas Lehn's own synth-squalls years later, and would surface in tone and concept amongst labels such as Erstwhile, Grob, and Creative Sources. In a word: seminal.

Comments and Feedback:

|